Targeted cyberattacks against critical infrastructure (CI) are increasing on a global scale. Critical systems are rapidly being connected to the internet, affording attackers opportunities to target virtual systems that operate and monitor physical structures and physical processes through various modes of cyberattack.

When people think of cyberattacks, their minds often go first to the financial sector. After all, that’s the type of attack people hear about most frequently; it’s where the money is and it’s what seems most natural for cybercriminals to target. Enterprises frequently focus on such cyber-enabled financial crimes to the point that they give too little thought to attacks that target CI. Among the rapidly growing ranks of cyberattackers, however, motivations are far more varied.

Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and Internet of Things (IoT) give CI operators the ability to increasingly transition CI control to distant monitoring of remote systems. This increases efficiencies and cuts costs, but leaves those systems more vulnerable to both attack and degradation. That’s why I will focus in this article on the threats to those areas of CI that are less talked about – those that are outside the financial sector and those that are vulnerable to cyber-kinetic attacks – and examine how Canada is dealing with the real and present threats.

Having worked on critical infrastructure cyber protection in the US, UK, EU, Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong and the rest of Greater China, South Korea and other countries, I can compare the approaches with my new country – Canada.

The Changing Threat Landscape for Critical Infrastructure Cyber Protection

CI is at the core of the cyberwarfare worry. It’s a rapidly growing concern and, these days, the majority of countries are developing at least some defensive cyberwarfare capabilities. Furthermore, more than 30 countries are allegedly building offensive cyberwarfare capabilities. While few public examples exist of overt cyberwarfare, we see lots of cyberwarfare “positioning” – geopolitical adversaries breaking into each other’s CI in order to test defences and create footholds for future potential destructive attacks.

Traditional boundaries between cybersecurity concerns, however, are disappearing. As US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) noted last month: while “nation-states continue to present a considerable cyber threat,” non-state actors, too, “are emerging with capabilities that match those of sophisticated nation-states.”

Financially motivated cybercriminals came up with many innovative ways to monetize their craft and have started intentionally or inadvertently impacting CI. Over the last few years, a number of CI operations have been impacted by ransomware or cryptojacking infections for example.

We increasingly see hacktivists, agents of hostile countries, or potentially terrorists seeking to use cyberattacks to strike a blow for their cause or disrupt the lives of those they see as enemies.

We observed employees of some of the critical industries’ competitors (e.g., in critical manufacturing) seeking to harm those competitors through cyberattacks that give the attacker’s company a competitive advantage.

Disgruntled employees who work within critical systems seek revenge on employers they feel have wronged them, using cyber means to sabotage systems. Even individuals as seemingly benign as bored teens may launch attacks on digitized physical systems essential to our lives, simply to test how much of an impact they can have on them.

Attacks from all these vectors have occurred repeatedly.

Defining Critical Infrastructure (CI)

Every country has their own, unique definition of CI, and they don’t always include all the same industries. The Canadian government’s Public Safety Canada (PSC) website defines Canada’s CI as follows:

Critical infrastructure refers to processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government.

Its explanation of Canadian CI includes the following ten sectors: Health, Food, Finance, Water, Information and Communication Technology, Safety, Energy and Utilities, Manufacturing, Government, Transportation.

In reality, divisions are not entirely clear-cut. These sectors rely on one another heavily in order to function smoothly. A report by the McDonald-Laurier Institute states:

CI is so widely distributed and pervasive that it is impossible to say who is responsible and who is accountable for CI either as a system or a set of sub-systems. In fact, it can be argued that this is a case of multiple interests crossing all the normal divides of public and private to the degree that there is a real danger that even with titular leadership being lodged with Public Safety Canada, in the end no one is responsible and no one is accountable. In reality, the entire policy process is merely a combination of muddling through and ad hoc problem solving. When faced with an assault on key CI or its breakdown in the face of a natural disaster or total failure due to neglect, the responsibility to prevent, respond, and restore must be clear.

Yet, breaking them down is at least one step toward getting a handle on different parts of the interrelated whole. These sectors align closely with some of the sectors identified by other nations with which Canada most closely works – Australia, New Zealand, the UK and the US – in its efforts to develop a joint understanding of and cooperative effort toward how to protect those infrastructures.

Canadian and US critical infrastructure cyber protection cooperation

Because of their long, shared border and the vast number of interconnections that their proximity provides, Canada is especially closely aligned with US on CI issues. Canada and the US cooperate on CI cybersecurity, and on emergency and disaster management in numerous ways.

This cooperation is essential, because CI failures in one nation do not necessarily stop at the neighbouring country’s border. This is clearly demonstrated by the cascading power failure that blacked out much of the Northeastern US and Southeastern Canada on August 14, 2003, or the 2006 cascade failure that left 15 million Europeans across several countries without power. These examples show that small disruptions can have enormous effects, not just on the power grids themselves, but on all services – telecommunications, transportation, financial, health and emergency services – that rely on those grids.

The two nations have long cooperated in three key areas: building partnerships, increased information sharing and joint risk management. A joint Emergency Management Consultative Group oversees joint emergency management, promoting dialogue between stakeholders in both countries, including on CI issues. Sector-specific networks in both nations promote cross-border collaboration. A Critical Infrastructure Risk Analysis Cell also enables the nations to jointly enhance information-sharing and develop risk management and analytics tools that are equally effective on both sides of the border.

PSC endorses the NIST Framework, developed by the United States’ Department of Homeland Security (DHS) with the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), and acknowledges the relevance and applicability of the NIST Framework in the Canadian context.

In addition, the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre (CCIRC) works jointly with the US DHS’ United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team and Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team on several key initiatives. They facilitate real-time collaboration between analysts across both countries and help develop standardized incident management processes and escalation procedures. They also seek enhanced ways to more effectively communicate cybersecurity issues to the private sector and general public.

Canadian government agencies involved in cybersecurity

Canada also deals with CI issues through a number of internal agencies. The CCIRC serves as Canada’s computer security incident response team. It monitors and advises on cyber threats and coordinates the national response to any incidents. Also, the Cyber Security Cooperation Program helps owners and operators of vital cyber systems reduce vulnerabilities in Canada’s cyber systems through grants.

Many other departments and agencies also play roles in protecting CI. Departments like the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Communications Security Establishment and Defence Research and Development Canada form the front line in assessing and mitigating threats. The Department of Justice and Global Affairs Canada focuses on cyber-related legislation within Canada and helps shape multinational cyber law. And many other departments play specific roles to help provide a secure online environment and resilience.

Plans and successes

Although the National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure (published in 2009) didn’t mention cybersecurity specifically, it set high-level guidelines that formed the foundation for the strategies that developed from it. Most notably, it established the National Cross-Sector Forum (NCSF), which publishes regular action plans for CI. These plans have fostered collaboration between the federal government, provincial/territorial governments and CI owners and operators in sharing information, developing policies to protect CI and enhancing its resilience.

The Regional Resilience Assessment Program (RRAP) enables government officials to work directly with CI owners and operators to identify vulnerabilities, assess threats and develop strategies to reduce exposures. The Virtual Risk Assessment Cell (VRAC) provides experts to help the CI community identify impacts of potential threats and improve response planning for disruptive events.

The NCSF’s Fundamentals of Cyber Security for Canada’s CI Community offers industries specific steps they can take to achieve baseline levels of cybersecurity recommended in the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. It also identifies measurement indicators and further resources for building greater resilience.

The government is currently updating its Cybersecurity Strategy. In 2016 it held public consultation on cybersecurity and the consultation report was issued in January 2017. In addition, PSC also offers a free, one-day cybersecurity assessment to organizations and has a certification program in the works for CI operators.

Many other successes have occurred over the years. PSC issued guidances and mandates for all sizes and all industries; helped strengthen the reporting of cyber-crime and developed Cyber Incident Management Framework for Canada; forged partnerships with cyber professional associations; and much more.

As the threat environment continues to evolve, so do these groups and programs. They continue to meet with and deepen relationships between international partners, different levels of government and the private sector, constantly reassessing vulnerabilities and seeking to strengthen resilience. They continue to build on past successes. Clearly those involved in protecting Canadian CI take cybersecurity seriously.

Room for improvement

That is not to say that Canada cannot not do even better in mitigating the risks to which Canada’s CI is vulnerable.

Despite all the achievements, I believe Canada still lags behind many of its peer countries and could do better in CI protection. Bear in mind that my opinions are based only on public sources and my discussions with Canadian CI operators. I am not speaking as someone with insider info not known to the public.

In fairness, I must state that the Canadian government is confident – based on the report of Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale at a March 1, 2018, CyberCanada Conference – in its present efforts toward preparedness. Based on what I see from my perspective, however, I feel some areas could be further improved.

Cyber-kinetic attacks, Internet of Things (IoT) and Intentional Electromagnetic Interference (IEMI)

One area that concerns me is the lack of awareness of cyber-kinetic attacks. I believe this area is becoming the greatest cyber threat but is often overlooked outside of the small, specialized subset of national cyber defence organizations.

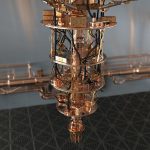

Industries are rapidly connecting Industrial Control Systems (ICSes) to the internet. Such systems’ principal security approach in the past had been the fact that they were physical features attached to physical systems in secured buildings. Increasingly, though, over recent years, they have been connected to the internet. By doing this, efficiencies are multiplied but so are vulnerabilities. Failing to account for the security vulnerabilities and all the potential security and safety impacts such access creates is risky at best and could prove disastrous.

Similarly, Internet of Things (IoT) solutions are rapidly proliferating across all society – and especially in CI, where they offer the opportunity to gather and analyse data at minute levels never before possible. In most cases, these come to market with far too little thought given to security.

Those demanding IoT solutions focus more on the efficiencies they increase than on the risks they create. Meanwhile, those supplying the demand often give little thought to the question – namely, how these devices are secured – that prospective customers are not asking. With the IoT, the attack surface is greatly expanding, far beyond the previous legacy ICS technology. This must be explicitly recognized and addressed in CI cyber protection approaches.

To complicate things further – IoT devices are even more geographically distributed than legacy ICS and access to them cannot easily be physically controlled. With such geographical distribution, increasing interdependencies, constantly decreasing power requirements and increasing communication over low-power networks, threats of Intentional Electromagnetic Interference (IEMI) to IoT used in CI is rapidly growing and should be addressed together with cybersecurity approaches to CI protection.

Cybersecurity in Canadian industries

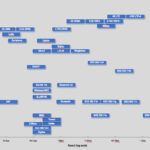

According to data from IDC Canada’s IT Advisory Panel, 2017 (June 2017), infrastructure services was the largest adopter of IoT solutions, with 77% of them using IoT in some form in their production, another 2% having IoT in pilot programs or proof of concept and 19% considering adoption in mid-2017. That places 98% of that sector either actively using or likely to soon adopt IoT functions, with other industries not far behind.

What makes this concerning is the result of interviews of 296 Canadian executives on the matter of cybersecurity. Only 52% stated that security strategies were addressed at the highest level of their organizations. The majority were most concerned about threats against traditional cyberattack information targets: proprietary information and customer data. Only 26% saw cyberattacks as a threat to physical property and 22% to human life, although nearly half (49%) acknowledged the threat of cyberattacks disrupting operations.

Even more concerning is the low level of security testing described by respondents. Only 40% run penetration testing; 37% conduct threat assessments; 41% conduct vulnerability assessments; and 38% actively monitor information security intelligence. Even assuming those numbers are higher in the CI community, they are still disturbing, considering the domino effect possible in a highly interconnected digital world.

Gaps in governmental statements

Although the Canadian government has clearly taken cybersecurity seriously, its approach to the concept of cyber-kinetic attacks is surprisingly vague. The bedrock document on the need to secure CI, its National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure, doesn’t mention cyber threats at all. Granted, it may not be fair to point to a document drafted in 2009 for not focusing more heavily on the threats that have become more prominent in the past decade, but more recent documents also seem to touch on the issue only lightly, if at all.

Fundamentals of Cyber Security for Canada’s CI Community, published in 2016, describes the risk to CI by saying, “Critical infrastructure sectors are interconnected and dependent upon secure cyber systems, and cyber disruptions to critical infrastructure can have significant economic implications – creating the potential of extensive losses for businesses and negatively affecting local, national and global economies.” This assessment is good but doesn’t go far enough. It doesn’t explicitly mention risks to the physical world and safety risks to people. It talks only about economic implications.

Or consider Canada’s official definition of a cyberattack: “[T]he unintentional or unauthorized access, use, manipulation, interruption or destruction (via electronic means) of electronic information and/or the electronic and physical infrastructure used to process, communicate and/or store that information.” While being good as far as it goes, it, too, appears to overlook the threat of cyber-kinetic attacks.

It appears to focus merely on information. Certainly, one could extrapolate this to include cyber-kinetic attacks by saying that every Cyber-Physical System (CPS) – whether ICS or IoT – at its root, is merely processing information. It would seem wise, though, to recognize the very real affect that digitally connected systems have on our physical world, delivering critical services such as water, electricity, transportation and even – to a growing degree – our food and our health care. We’re not talking just about disrupted data here; we’re talking about lives, well-being and the environment.

The much older (2001) Canadian Anti-Terrorism Act comes closer on this point by defining cyber terrorism as an act of causing interference with the disruption of essential service by using the internet facilities or a computer system, to result in the conduct of harm to the federal government of Canada and its citizens. Yet even this cyber-terrorism definition focuses only on disruption of services.

The one description that addresses the issue of cyber-kinetic attack that I found in the public documents I reviewed was in the recent National Cross Sector Forum 2018-2020 Action Plan for Critical Infrastructure. It stated:

[T]he increased reliance of organizations on cyber systems and technologies creates exposure to new risks that could produce significant physical consequences. ICS are at the intersection of the cyber and physical security domains. These systems, many of which were developed prior to the internet era, are used in a variety of critical applications, including within the energy and utilities, transportation, health, manufacturing, food and water sectors. For a variety of reasons, including efforts to minimize costs and increase efficiencies, these systems are increasingly connected to the internet, which can result in exposure to more advanced threats than those considered at the time of their design.

It’s good to see that the physical impacts of cyberattacks are slowly being recognized. Yet, even in the rest of this document it mentions only ICS, which is unnecessarily specific. It makes no mention of IoT, robotics, autonomous transportation, medical devices, etc. The authors might want to consider using the term “cyber-physical systems” as the broadest term that encompasses all the others.

In my opinion, recognition of cyber-kinetic risks – or, physical impact risks of cyberattacks – in Canada lags behind many other countries with which I have worked. Even though the most recent documents are beginning to mention cyber-kinetic risks, those documents still don’t mention IoT.

CI providers are rapidly digitizing and adopting new technologies such as IoT, robotics, autonomous transportation, drones and many others. As they do, the physical impacts of cyberattacks are becoming increasingly important. We need to recognize this and prepare accordingly. Not only that, but the government should take a stronger leading role in protecting its people from this growing threat.

Problems with funding

Another issue is the matter of underfunding cybersecurity efforts. British Columbia Senator Mobina Jaffer pointed out that while countries like the US, UK and Australia are budgeting billions for cybersecurity, Canada’s budget for 2018 was only CA$77.4 million.

Canadian Finance Minister Bill Morneau outlined the plans to spend CA$500 million on cybersecurity initiatives over the next five years in his 2018 federal government budget. After that initial period, the government will set aside CA$108 million a year for continuing cybersecurity initiatives. It is a significant improvement and a movement in the right direction. However, in my mind it is still not commensurate with risks. For comparison, the United States spends US$15 billion a year on cybersecurity.

A speaker at the CyberCanada Conference was not as optimistic about Canada’s cybersecurity readiness as Public Safety Minister Goodale had been. Melissa Hathaway, former cybersecurity advisor to US presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, fellow at the Canadian Centre for International Governance Innovation and president of Hathaway Global Strategies, pointed out a discrepancy between what government officials say and the level of funding designated to achieve those goals.

She said of Goodale’s aspiration to see Canada as a leading digital economy:

“ …there’s not an underlying ‘How do I make it resilient, secure and safe?’ You can’t have an economic vision taking the country in one direction and then security and resilience on the back burner. They have to be of equal importance.”

The PSC free cybersecurity assessment program and certification programs are a good example of this. While they are great initiatives by PSC and valuable steps toward mitigating vulnerabilities, their benefits to improving overall cybersecurity posture of Canadian CI could be better. The assessment program and upcoming certification program are voluntary. So far only a small percentage of Canadian CI organizations have taken this free assessment. Assessments, being quite short (2-3 days), can only scratch the surface. It apparently takes a long time for PSC to issue the report to the CI operator. And based on my discussions with CI operators, they rarely take advantage of further follow-ups with PSC.

PSC efforts at forming partnerships are worthwhile. It must be acknowledged, though, that getting people talking is only a starting point, not a final destination.

Even there, weaknesses exist. Organizations that have been breached often are reluctant to disclose breaches, fearful of losing the public’s confidence and damaging their brand. Such fears are being mitigated somewhat by the new mandatory breach notification – although it focuses on data breach of personal data – and by the existence of the Canadian Cyber Threat Exchange, a not-for-profit, independent organization to which organizations can disclose attacks with confidence that their data will be anonymized before it is analysed or shared. This is a step in the right direction, but reluctance still exists, impairing solid analysis.

What others are doing

Is this just a matter of semantics, though? Is the terminology that Canadian policy documents use insignificant, or does it reflect a position that is leaving it behind other countries in the world community?

Having worked in other countries on those issues puts me in a position to share what I have seen there. There is a broad-scale recognition among policy makers in all the countries I mentioned that collaborative efforts between public and private sectors are required to develop and enforce effective CI protection. Different jurisdictions, however, approach it differently.

UK

In 2010, the British government recognized cybersecurity as a “Tier One risk” to its economic and national security. UK cybersecurity strategy also recognizes that “The ‘Internet of Things’ creates new opportunities for exploitation and increases the potential impact of attacks which have the potential to cause physical damage, injury to persons and, in a worst case scenario, death.”

In an effort to comply with the EU Network and Information Systems (NIS) Directive, the UK government announced in January that UK CI operators could face fines of up to £17 million (~CA$30 million) if they do not have adequate cybersecurity measures in place.

In 2016, the British government announced its plans to almost double its investment in cybersecurity – up to a maximum of £1.9 billion (~CA$ 3.6 billion) in new funding over the next five years.

The UK has conducted several national cybersecurity exercises in collaboration with industry to practice crisis response plans for government agencies and specific operators of CI. For instance, in November 2013, the Bank of England conducted the “Waking Shark II Cyber Security Exercise” – a stress-test exercise developed to evaluate the response of the wholesale banking sector to a simulated cyberattack.

China

Over the last few years, China has included CI protection in numerous government strategy documents, laws and regulations. This includes their controversial Cybersecurity Law that gives the government broad powers to spot-check networks within Chinese borders and requires that data generated in China also be stored in China.

Interestingly, in addition to traditional CI sectors, China also includes large-scale commercial internet services, including search and social media, in their CI definition.

China’s Ministry of Public Security has also been managing its risk-based security certification – Multi-Level Protection Scheme (MLPS) – compliance for years.

In contrast to Canada, China, in many ways, takes a very hands-on approach to CI protection, from enforcing compliance with regulations to stepping in when CI incidents occur. This is easier to execute there, of course, because most CI operators in China are state-owned – apart from the internet web service sector – whereas in Canada, Europe and the US, CI operators are mostly privately owned.

EU

Similarly, the EU has moved steadily toward greater standardization of cybersecurity and notification requirements across member states. Back in 2014, France passed the first mandatory CI cybersecurity installation and maintenance requirements. Germany followed in 2015 with legislation that imposed stiff monetary penalties for noncompliance with mandatory standards.

The EU has since followed with its Network and Information Security Directive (NIS Directive), which took effect in 2016 and required that all member nations transpose the directive’s mandatory standards into their own national law by mid-2018. This directive takes cybersecurity standards EU-wide, targeting “operators of essential services” (OESes) – which is the EU term for CI providers. The directive will carry significant fines.

There, as with China, the nature of the governmental body made it easier to develop and enforce stricter standards. In China’s case, it was their control of state-run CI providers. In the EU, it was the extreme interconnectedness of CI between the nations that motivated standardization across the continent.

In addition to country-level cyber exercises that the likes of UK, Germany or others perform, ENISA (European Union Agency for Network and Information Security) manages the programme of pan-European exercises named Cyber Europe. This is a series of biennial EU-level cyber incident and crisis management exercises involving both the public and private sectors. The Cyber Europe exercises are simulations of large-scale cybersecurity incidents that escalate to become cyber crises.

US

Canada perhaps comes closest in its approach to the US because of its shared geographic space and interconnected CI. The nature of their geographic proximity and interconnected CI is markedly different from the partnership between EU nations, though, and that difference is what is likely responsible for Canada and the US lagging behind.

Sharing of resources and CI involves far more partners in the EU, motivating nations to a higher degree of standardization. Sharing of resources and CI between Canada and the US, on the other hand, is far more limited, with both countries being vast enough in size that even their long, shared border represents only a small volume of interaction compared to what EU nations experience.

Yet, even though Canada and the US have much in common in their approaches to CI vulnerabilities, the US still appears to stand significantly ahead of Canada in addressing them. For example, the US DHS has defined a more comprehensive CI definition than that adopted in Canada or in the UK/EU within the NIS Directive. The US recognizes 16 CI sectors compared to Canada’s 10, including also the chemical industry, dams, the defence industry and emergency services, and breaking other Canadian sectors into separate entities for more comprehensive attention.

US President Barak Obama’s 2013 Executive Order – Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity – tasked the US to lead the development of a framework to minimize cybersecurity risks to CI. It sought feedback from public and private sector stakeholders and incorporated industry best practices to the fullest extent possible.

The framework developed by the US NIST in 2014 has had much broader success in achieving adoption by US CI providers than Canadian efforts have had. Many key US stakeholders, including the private sector, actively participated in its development and made adaptations in its implementation to meet their respective security needs.

PSC has endorsed the NIST Framework but doesn’t enforce it in the same way. And the private sector organizations, unfortunately, have not bought into it in the same way that US organizations have. Even though approximately 85% of CI in the US is privately owned and free-market principles typically steer US industry, the US government is more hands-on in CI protection than Canada has been.

Not only has the US’ strong Department of Homeland Security been effective in encouraging compliance, but also the US military has been deeply involved in domestic affairs regarding cybersecurity. This is surprising, because US constitutional power-sharing principles prohibit the military from policing inside the US. But this only goes to show how seriously the US approaches the cyber protection of its CI.

Singapore

In 2015, Singapore established the overarching cybersecurity agency – The Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA). The CSA is a Singaporean government agency under the Prime Minister’s Office that provides centralised oversight of national cybersecurity functions and works with public and private sector leads to protect Singapore’s critical services.

Singapore’s Cybersecurity Bill was officially passed into law in February 2018. The new Act applies to “any critical information infrastructure located wholly or partly in Singapore.” A critical information infrastructure (CII) is any “computer or computer system” deemed necessary for the continuous delivery of Singapore’s 11 primary essential services. Essential services are considered any service that, if compromised, would have a “debilitating impact on the national security, defense, foreign relations, economy, public health, public safety or order of Singapore.”

Under the new law, those entities considered to be CII providers will be required to report cybersecurity events to the CSA. Additionally, CIIs will be required to report on technical architecture related to interconnected infrastructure, conduct regular compliance audits and ongoing risk assessments, as well as participate in required cybersecurity exercises put in place by the Commissioner. Failure to comply with the new development will results in financial penalties of up to US$100,000 and/or two years in jail.

Recommendations

In Canada, the threat of cyber-kinetic attacks does not appear to be as recognized as elsewhere. Neither are the growing risks to CI coming from the IoT adoption. Canada, more than any other country I know, has a hands-off approach. While it tries to encourage information sharing and collaboration – and has had some successes in it – it doesn’t get involved directly in CI protection as much as other nations.

- In my view, CI is only as strong as is weakest link. I believe that Canada should develop mandatory standards across CI and more strictly enforce them. If mandatory standards are not implemented, voluntary programs and activities will leave too many gaps.

- This implies that government agencies should receive more authority to establish, to direct and to enforce compliance with cybersecurity standards.

- Cyber-kinetic threats – i.e., cyber threats to well-being, lives or the environment – should be given more importance in government initiatives – from awareness to policy formulation, controls definition and crisis and emergency exercising.

- Related to above, it only makes sense that cybersecurity emerge from its silo and form a closer cooperation between cybersecurity, engineering, safety and emergency management teams at and across CI operators. This is another area in which the government could play a role – by raising awareness, developing frameworks that cut across traditional silos and facilitating or demanding cross-silo crisis exercises.

- Canada’s NCSF and other relevant organizations need to continue their work in updating and aligning national cybersecurity strategies with the ever-evolving world of cyberthreats. IoT is a current threat that should be addressed already now. Even though both – ICS and IoT – could be defined as cyber-physical systems, there are some IoT-specific threats and approaches. Intentional Electromagnetic Interference (IEMI) is another type of IoT vulnerability that should be considered. Artificial Intelligence (AI) introduces a whole new set of threats and vulnerabilities. While AI adoption is still slow within CI operators, we should start thinking about it now, as we should also with quantum computing.

- Canada should also consider using more sector-wide crisis exercises, similar to the biennial sector-wide crisis exercises conducted by the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA). Such exercises are regularly performed not only by EU, but by almost all other G7 countries and many others, such as Singapore. The midst of an all-but-inevitable cybersecurity crisis is not a good time to test the CI cyber response plan.

- The government could also provide stronger liability protection for organizations that voluntarily share critical information, so as to better benefit from the successes so far. This is a common problem everywhere – private sector organizations fear that sharing sensitive information would open them up to penalties or civil suits affecting reputations and profit. If Canada wants to be hands-off and rely on voluntary collaboration and on private companies doing the right thing, it should consider innovative approaches to make that collaboration effective.

- A 2017 study by PSC shows some concerning failures in carrying out Canada’s cybersecurity strategies, such as inadequate documentation by oversight bodies that make it impossible to assess those bodies’ effectiveness in carrying out their responsibilities, or confusion between oversight bodies regarding what responsibilities fall within their domain. To PSC’s credit, these gaps are being identified and addressed. Correcting these and other flaws in governance must continue.

- Yet even with strong government leadership, securing Canada’s CI is not a simple task. Much of Canada’s CI lies in the hands of a wide variety of private organizations. Without their buy-in, there will be only slow progress. Thus, there should also be more awareness activities across private CI operators and the general public.

Canada has made a good start on this but needs to keep pressing the point. Private owners will address risks to the degree that they are aware of them. They will balk at investing beyond what they feel meets those risks and often will underestimate risks until they are convinced that those risks pose a clear and present threat. Whether through stronger mandatory standards or increased awareness of the scope of threats, government can help motivate private owners to make the decisions necessary for increased security.

Does it really matter?

General opinion outside of the Canadian government sometimes appears unconcerned about the possibility of attacks on Canadian CI. The common thought is that cyberattackers are so focused on the US that they have no interest in attacking Canadian interests. Or, as quite a few of my interlocutors put it “We are Canadians. We are friends with everybody. Why would anybody attack us?”

I don’t agree with that, though. For one, Canada and the US have significant inter-dependencies. Impacts on the US could cascade into Canada. Also, if attackers seeking to disrupt US interests find greater vigilance in protecting CI on the US side of the border, they are likely to turn to Canadian CI, hoping their efforts can start a cascade that causes disruption in the US.

Such is the case with the recent alert issued by the US Computer Emergency Readiness Team. This alert warned of efforts by Russian state actors to compromise both US and Canadian networks in energy, nuclear, aviation, critical manufacturing facilities and others to gather intelligence on the ICSes that control processes there.

The CCIRC’s 2018 report for the year 2017 also described an ongoing campaign of malicious cyber incidents that reveal a high degree of effort to compromise Canada’s electrical grids and nuclear facilities, as well as lesser efforts directed against financial, academic and critical manufacturing sectors. The report also showed a growing trend toward targeting hospital systems and network-connected medical devices.

It is nothing but wishful thinking to believe that no one is targeting Canada. Canada is indeed being heavily targeted. A 2013 study of hacker forums came to some disturbing conclusions:

Through data mining of data and manual revision, this study sought to identify information pertinent to critical infrastructures, with specific emphasis on Canadian systems, posted to publicly accessible hacker forums. Results indicate that Canadian IP addresses were overrepresented in the data, meaning that Canadian critical systems are of particular interest to hacker forum users…

This prevalence of Canadian IP addresses across hacker forums highlights the potential threats to Canadian systems. In addition, a 2017 study showed that 38% of Canadians had been victimized by cybercrime in the previous year. A 2018 study reported that Canada is the No. 1 target for phishing scams. Another 2017 study of cybersecurity readiness showed the organizations that reported a breach that exposed sensitive data had increased by 46% since 2014 and that the number of organizations that believe their organizations are winning the war against hackers dropped from 41% to 34% over the same time period.

A 2013 study showed that 69% of Canadian businesses had suffered some kind of attack in the previous 12-month period. The idea that nobody’s interested in targeting Canada is blatantly false.

Even in 2012, security experts were recognizing the growing threat: “Given the rapid changes in information and communication technologies, the Canadian government is not alone in concluding that existing defences will not be enough to ensure the integrity and availability of its information systems nor prevent critical infrastructure from being destroyed or shut down.”

Takeaways

With an estimated 21 billion devices and 212 billion sensor-enabled objects predicted to be part of the IoT by 2020, it is essential to ensure that cyberspace is secure, particularly where it applies to CI. Realistically, it can be said that making CI absolutely secure is unrealistic. Situations change rapidly, new technologies are constantly being incorporated, vulnerabilities and risks continually evolve. You can’t confine such a moving target – especially one whose purpose is to be open enough to deliver services to the public.

Continually building more robust CI, however, is essential for the safety and security of Canada and its citizens. We cannot eliminate all possibility of disruptions, but we can work to ensure that they are as few and as limited in scope as possible.

What we can come closest to calling a solution, I believe, involves three elements: Continue to work toward bringing all stakeholders into a greater awareness of vulnerabilities and threats; Achieve a better understanding of the different ways that public and private stakeholders perceive risks; Facilitate the flow of information so all parties can work together to form strategies that provide the best possible protections against the wide variety of threats.

No one strategy and no one tool will suffice. Complex and interconnected issues like this require complex and interconnected efforts that involve all stakeholders. But with continued effort, Canadian stakeholders can better protect its CI – and its citizens.

For over 30 years, Marin Ivezic has been protecting people, critical infrastructure, enterprises, and the environment against cyber-caused physical damage. He brings together cybersecurity, cyber-physical systems security, operational resilience, and safety approaches to comprehensively address such cyber-kinetic risk.

Marin leads Industrial and IoT Security and 5G Security at PwC. Previously he held multiple interim CISO and technology leadership roles in Global 2000 companies. He advised over a dozen countries on national-level cybersecurity strategies.