Western publications often picture the People’s Democratic Republic of China (hereafter China) as the world’s chief propagator of cyberattacks. But the picture is much more complex than such broad-brush claims suggest.

Few Westerners realize that China and its neighbours in the Greater China region (Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong) have, over last few years, became the most technologically advanced region in the world – ahead of the West in the adoption, and in many cases even in the development of advanced technologies.

Countries in the region were always close to the top of the list of victims of cyberattacks. Factors, such as internal hacktivism and cybercrime perpetrated by the rapidly growing technologically savvy segment of the population and their legion of wannabe hacker apprentices have propelled cyberattacks on the region firmly to the top of that list.

Rapid adoption of new technologies without adequately addressing cybersecurity issues only exacerbates the problem. The Greater China region has adopted these technologies aggressively. Yet, in their rush to adoption, enterprises in the region have largely lagged the rest of the world in addressing cybersecurity.

The rapid growth of advanced technologies, coupled with the slower growth of the cybersecurity measures necessary to protect them, has left the Greater China region vulnerable to increased cyberattacks focused on traditional cybercrime, cyber-physical system attacks that could impact the region’s rapidly “smartified” infrastructure, and cybercrime reputational consequences that could devastate region’s economic development aspirations that are increasingly linked to technology adoption and technology exports.

A History of Chinese cybercrime vulnerability

First instances of computer crime in China started appearing in mid-1980s with the banking systems being the first victims of insider computer-enabled crimes.

Forms of hacktivism started fairly early in China with first political viruses emerging in 1989.

Internet in China became commercially available in 1995 and since then the Internet have seen explosive growth in China. This was closely followed by various forms of cybercrime. Patriotic hacking was the first to appear which led to emergence of the Green Army hacker group in 1997, that later gave way to the Red Hacker Alliance, a loosely connected set of groups that emerged after the Jakarta riots of 1998, when Chinese nationals were accused of destabilizing the country. Indonesian websites were defaced by outraged Chinese hackers, and a nationalistic movement took on force.

Since then, for-profit motives have emerged and cybercriminals have increasingly started focusing on attacking Chinese IP addresses that were previously protected by the hackers’ nationalism. While Russian cybercriminals, for example, are still today reluctant to attack Russian systems, partially because of patriotism and partially because of the local legal system, those deterrents disappeared in China almost 20 years ago putting the newly connected Chinese society at the cross-hairs of domestic cybercriminals.

Chinese officials first voiced public concern about cybercrime against their citizens in 2001. Over the coming years, a cybercrime subculture exploded fueled by the lack of cyber protection as well as the economic changes. Growing unemployment of mid-2000s led to a large number of young unemployed people trying their luck in cybercrime. Online crimewave started spreading to different industries and even smaller and remote cities in some of which phishing and other cybercrime has started supplanting traditional crimes. Most hackers were technologically unsophisticated, buying pre-packaged hacking tools from professional hackers on the underground Internet. Chinese law enforcement focused on shutting down online marketplaces where these tools were sold, but with mixed success.

Following the ancient Chinese tradition of a pupil apprenticing oneself to a master, the growing industry of selling tools spawned a hacker training industry, as well. Cybercrime increasingly spread from simple phishing, a crime against individuals, to attacks on financial institutions. In the next five years, Chinese officials shut down some of the largest online marketplaces and training sites, but cybercrime still skyrocketed.

A 2008 announcement by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) estimated that 1.2 million Chinese computers were infected by software that allowed attackers to control them as part of a botnet (a network of compromised computers that a hacker can control remotely without the owner’s knowledge). This made China home to approximately 60% of computers in the world thus infected. The huge amount of computers infected and participating in botnets explains, to large extent, the perception of China as the chief perpetrator of cyberattacks. While the botnets might have been controlled by cybercriminals from anywhere in the world, to the victims it would have appeared like the attacks were coming from China. A 2009 government report claimed 7.6 billion Yuan (US$1.2 billion) in economic losses.

The scope of attacks has continued growing, as well. A massive cyberattack forced the Hong Kong stock exchange to temporarily suspend trading of seven major companies in 2011. Although trading systems were not believed to have been compromised, investors were temporarily blocked from receiving crucial announcements scheduled for release by those companies. The Norton 2012 Cybercrime Report listed 85% of Chinese citizens as having been victims of cybercrime – the highest percentage of any nation’s citizens. VTech, a Hong Kong toy company, suffered a 2015 attack that exposed the personal information of 4.9 million adult customers and their 6.4 million children. In 2015, Taobao, a Chinese consumer-to-consumer sales platform like the US eBay, saw 21 million of their members’ accounts compromised in a massive scheme to give the appearance of legitimacy to fraudulent sales offers. A 2015 government report places the yearly impact of cybercrime to China’s economy at 80.5 billion Yuan (US$11.9 billion). Clearly, cybercrime has already had a major effect on the Chinese economy.

Advanced technology adoption in China

This explosion of cybercrime occurs as the Chinese government seeks to emerge as the chief global superpower by means of outpacing the West in technology. To accomplish this, it encourages Chinese businesses to adopt the newest, most advanced in technologies.

Internet of Things (IoT)

Chinese adoption of the Internet of Things (IoT) grows at a frantic pace. So great is the appetite for this technology that Western IoT-focused companies anticipate that their sales to China alone will outpace sales to all other markets combined. Add that to the fact that China is not only the No. 1 buyer of IoT technology, but also the leading manufacturer and exporter of it and you get a startling picture of how pivotal IoT is to the Chinese economy.

The rush to adopt IoT, however, is driven more by excitement over its potential than by strategy. According to Chee We Ng, a Cisco investment professional based in Shanghai, “People don’t know what will stick but they know they don’t want to be left behind. In the US especially, … big firms will go out and do market research and try to understand what the internet of things will mean for their business, but in China, there’s less worry about the implications.” While this less-constrained thinking can facilitate unexpected partnerships and visionary breakthroughs, it also opens the doors to further vulnerabilities.

Those vulnerabilities are the one thing that could derail China’s hopes of leading the way into IoT’s promise of a more connected world. Lax cybersecurity practices in components built by a Chinese manufacturer enabled hackers to infect hundreds of thousands of devices that then were used in a massive DDoS attack that slowed the Internet in October 2016 and paralyzed Twitter, Spotify, PayPal and other major sites.

Smart Cities

China has aggressively developed smart cities, which monitor and seek to control such common urban challenges as pollution, traffic congestion and widespread energy consumption through connected technologies. The government’s 12th Five-Year Plan announced in 2013 included the development of 103 smart cities, districts and towns.

Initial development focused on optimizing individual city functions for greater connectivity and control. Smart city development, however, increasingly connects individual systems into platforms that offer more centralized control of entire city functions leading to a whole host of potential cyber-caused disruptions, not to mention an unprecedented amount of data on individual citizens whose movements and actions interact with smart city systems through the smartphones they use to access them.

Smart Grid

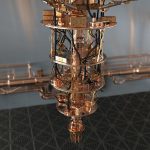

China is the world’s largest consumer of electricity, and its demand is expected to triple by 2035. To address the demand, implement China’s new clean energy goals and improve the reliability of the country’s existing infrastructure requires a smart grid – next generation of electrical grid that achieves efficiency by connecting the traditional operations technology with modern digital and communications technologies. China has already invested hundreds of US$ billions in smart grid development and its annual smart grid development investment is estimated to reach US$128 billion between 2016 and 2030 comprising anywhere between 24% and 50% of the global smart grid investment based on various analysts.

Chinese smart grids ambitions don’t stop at addressing own energy demands. The State Grid Corporation of China has embarked on a global buying spree building towards a China-controlled global “Internet of energy”.

As it continues its adoption of smart grid technologies, China is also increasingly developing them domestically with target costs up to 65% lower than those of EU or US-developed technologies. As a part of the national critical infrastructure the energy grid in China will remain well protected by the cyber capable Chinese government. The concern remains, however, about the security of smart grid technologies China exports.

Smart Manufacturing

China similarly seeks to apply IoT to its industries. Already No. 1 in the world in manufacturing, it seeks to extend its lead by expanding machines’ ability to communicate with each other and with the goods they produce. The financial benefits of accomplishing this are staggering. Research firm IDC forecasts a revenue increase for China from US$193 billion in 2015 to US$361 billion in 2020 from smart manufacturing, and Accenture foresees it adding US$736 billion to China’s GDP by 2030.

Such results will not come easily, though. Despite China’s massive manufacturing capacity, a mindset that, for decades, focused on cutting costs leaves many manufacturing facilities with an overwhelming climb to achieve the needed upgrades. If pressure to upgrade escalates, security of new systems may suffer.

Smart Vehicles

China already manufactures more cars than any other country (more than twice as many as manufactured in the US in 2015) per the International Organization of Automobile Manufacturers (OICA). And the technology of Chinese cars rapidly approaches other countries’ automobile industries. While Tesla and Google Car enjoy the Western media spotlight, China quietly develops their own next generation of connected and self-driving vehicles.

The government’s ability to establish a uniform framework of standards may enable China to leapfrog Western nations, whose multiple governmental units and manufacturers still struggle to distill a chaotic patchwork of competing standards into a framework on which they all agree.

While this enhances speed to market, it also potentially leaves crucial legal, cybersecurity, and other considerations lagging. It can even embolden developers to scrap more proven technologies to leap into more advanced, but less proven, technologies to form the operational foundation.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Robotics

China has recently eclipsed the US and the rest of the world in AI, deep learning and robotics research and funding. In 2015 China spent three times as much on implementation of robotics than US. China is the largest buyer of industrial robots making up 25% of the global market. Its share of the global market is forecast to rise to 38% by next year. Foxconn alone, a key manufacturing partner for Apple, Google, Amazon, and the world’s 10th largest employer, has already replaced 60,000 workers with robots.

Chinese cybercrime threats and vulnerabilities

The speed with which China pursues new technology adoption increases the cyber risk that Chinese businesses and individuals already face, as well as cyber risks that China will introduce to the rest of the world as it starts increasingly exporting its technology.

The rush to technological advancement and its consequent vulnerabilities

As discussed earlier, China has been a huge target for cybercrime for the better part of the past two decades, with cybercrime there growing dramatically in the past six years. The Chinese government recognizes this, but the Chinese goal of becoming the world’s economic superpower results in conflicting approaches to cybersecurity.

The Chinese government is one of the front-runners in cybersecurity expertise, investing heavily in developing advanced capabilities for its government infrastructure and critical services. Those capabilities alone will not elevate China to the government’s goal, though. It also needs its economy to be preeminent among world economies.

When it comes to the businesses that constitute its economy, the cybersecurity situation is less developed. Rapid technological development and its drive of economic development is often seen as too important to be hindered by onerous cybersecurity and IT quality efforts.

While China has developed parallel and comprehensive standards in software, hardware and encryption and is continuing the development of related regulations, adoption of those standards in general business is largely lacking. Effort in that direction could slow the speed of achieving technological supremacy over foreign competitors.

So, Chinese companies gamble that the overall economic growth from rapid adoption will outweigh the losses that cyberattacks inflict on individual businesses. While Greater China region enterprises invest heavily in new technologies, they invest significantly less in cybersecurity than their peers in the US, Europe or even other parts of developed Asia-Pacific – and remain more vulnerable.

A further conundrum

While Chinese companies seem to be willing to take that gamble, they face another one, as well. Chinese reliance on Western software platforms has led to questions whether Chinese businesses are unknowingly accepting a position where its rivals could prevent Chinese companies from overtaking them.

According to Xinhua, the state news agency, in 2012 90% of microchips and 65% of firewalls in China originated in other countries, primarily the US. The concerns are that rivals could instruct Western software manufacturers to install backdoor vulnerabilities in systems sold to Chinese entities. If true, those actions could cripple the Chinese economy at will.

China is advancing rapidly in development of local operating systems, local app stores and other home-grown technologies earmarked for enhancing China’s independence in the IT sector. While improving rapidly, many are still less advanced than Western ones. Chinese entities thus find itself caught between two unpleasant choices. They can choose to live with those perceived vulnerabilities, or they can isolate themselves behind their own, proprietary platforms. With the first option, they face ongoing uncertainty. With the second option, they risk hampering their ability to compete in a global marketplace and perhaps even risk falling behind the world’s technological curve.

Threats to China from outside

As much as Western media focuses on cyberattacks that China launches on Western nations, the West has not been shy about reciprocating. China views US motives as mirroring their own: to dominate cyberspace so that they can maintain global pre-eminence and economic power. They view the US as an ever-present threat to launch cyberattacks against them to squelch Chinese gains in economic and political power.

Threats to China from within

China also faces significant threats from within. The Chinese cybercrime underground increasingly leads the way in cybercriminal innovation.

For cybercriminals it was often easier to target vulnerable Chinese nongovernmental networks than those protected by other governments or global enterprises with significantly higher cybersecurity budgets. Unlike Russian and other prolific cybercrime organizations that primarily focused on targeting victims outside of their national borders, Chinese cybercriminals remained focused on the local market.

Even as cybercrime grew, government and law enforcement primarily focused on trying to shut down cybercrime marketplaces and training sites and rarely on deterring cybercrime by applying the impressive government cybersecurity expertise to vulnerable business networks. The continued willingness of Chinese businesses to accept some losses as a cost of rapid technological advancement created an environment where cybercrime could – and still does – thrive.

Threats from within, however, go deeper than the size of the cybercrime underground and are more complex than just the drive for rapid technological development. Equally, if not more, threatening is the antiquated mindset that many Chinese businesses hold.

Many of the Chinese hacking victims have their origins as low-cost export business. As such, they were focused on cutting costs. Cybersecurity was not a high priority to their leadership. They accepted only the costs required to manufacture, market and distribute their products while the websites that connect them to the world and databases that hold sensitive information were not deemed worth the expense. Effective cybersecurity to keep information confidential was deemed an unnecessary luxury.

Many Chinese businesses still eschew effective cybersecurity as a luxury. In this, the pressure to adopt ever more advanced technologies while downplaying the importance of protecting those technologies only reinforces their thinking. This mindset places businesses in the Greater China region at an ever-increasing risk.

The case for optimism?

The government appears to be responding to these conundrums with making cybersecurity a key priority. Chinese President Xi Jinping has been consistently speaking about the importance of cybersecurity and has put himself in charge of the new body to coordinate cybersecurity. China is investing significantly in development of local regulations and technologies, and has recently passed a wide-ranging cybersecurity law that includes restrictions on technology imported from outside of China. Although Western companies and governments have expressed concern over some provisions, the law at least shows government recognition that current vulnerabilities in Chinese industries must be addressed.

What’s at stake

Not only does a lax mindset toward cybersecurity put manufacturers at risk, but also consumers. Not only consumer information, but potentially consumer lives, well-being and the environment. As the digital world increasingly connects devices that impact people’s health and welfare, effective cybersecurity for those devices is crucial.

Consider the case of the DDoS attack on the heating and hot water systems in two apartment buildings in a small town in Finland. While that attack resulted in nothing more than a temporary inconvenience for a few people in a remote place, it points out the need to fully secure devices connected to the Internet – especially those that protect our lives.

An event like this may have been an isolated incident committed by an individual who wanted nothing more than to cause embarrassment to the building management. Or, it may have been a small-scale test of an attack strategy by someone who aspires to take what they learn from this test to build a strategy they can used to disrupt vital, life-preserving systems on the scale of the DDoS attack that “brought down the Internet” in October 2016.

Or consider number of other examples I outlined in my other article When hackers threaten your life – Introduction to cyber-physical systems security

Building effective cybersecurity into systems and devices is not an unnecessary luxury. It is vital.

Chinese cybercrime wrap-up

The Greater China region contains one of the fastest-growing and most technologically advanced economies in the world. Yet the more that businesses in this region under-emphasize cybersecurity, the more vulnerable they will become. Consequences of under-emphasizing protection of infrastructure and sensitive data could be devastating.

Companies that suffer public data breaches suffers disintegrated customer trust and lost sales for years to come. Countless Chinese companies face the same potential losses. Yet those losses pale in comparison to the dire consequences that would follow the compromise of vital, life-supporting systems on a scale even a small fraction of the size of the October 2016 DDoS attack on the Internet.

If China wants to remain the leading manufacturer of electronics and be the leading exporter of advanced technologies, they should consider their reputation. Cyberattacks repeatedly exploit the vulnerabilities of Chinese networks, infrastructures and devices. Those attacks lead potential buyers to question the safety of using Chinese devices, especially as those devices increasingly enter the realm where them being compromised could jeopardize lives, well-being or the environment. Even if consumers start becoming desensitized to data breaches, they would never accept physical risks of cyber kinetic attacks.

If Chinese manufacturers won’t care about potentially devastating physical impacts, the rest of the world will. They will vote with their wallets and employ other sources for these advanced technologies.

The biggest bet China is making for its economic growth is the development, adoption and export of advanced technologies such as IoT, AI, robotics and “smart” everything. The biggest threat to Chinese ambitions of dominating these new technological fields are the ongoing cyber vulnerabilities that afflict them.

For over 30 years, Marin Ivezic has been protecting people, critical infrastructure, enterprises, and the environment against cyber-caused physical damage. He brings together cybersecurity, cyber-physical systems security, operational resilience, and safety approaches to comprehensively address such cyber-kinetic risk.

Marin leads Industrial and IoT Security and 5G Security at PwC. Previously he held multiple interim CISO and technology leadership roles in Global 2000 companies. He advised over a dozen countries on national-level cybersecurity strategies.